From newly minted gardeners to avid urban farmers, everyone with a patch of land wants to grow an apple tree.

Other fruits – pears, cherries, figs, plums – are desirable, too, but there’s something about apples that call to us the loudest. That leads to people impulsively and ill-advisedly purchasing trees without putting in the proper amount of research.

“While apples grow well in this climate, they are not necessarily easy to grow,” said Erica Chernoh, a horticulturist with Oregon State University Extension Service. “They require regular maintenance and care.”

So, before heading to a nursery, loading a tree onto a cart and wheeling it up to the cash register, ask some questions. When choosing which variety to grow, think about flavor (sweet or tart or somewhere in between), height and disease resistance, Chernoh said. Only you can decide on taste, although some garden centers have fall tastings or you can buy up a bunch of different varieties and have yourself a blind taste test.

For homeowners, she recommends dwarf trees, which range from 8 to 10 feet tall, and are particularly popular and easy to find in nurseries.

“Dwarfs are so much easier to manage,” Chernoh said. “You don’t have to climb a ladder to harvest or prune. And they fit well in the small lots many of us live on.”

If you fail to consider the first two characteristics, don’t neglect to find out how well your potential tree can fight off diseases. Apples are susceptible to a whole bucket of diseases like powdery mildew, apple scab and anthracnose. Reputable nurseries should be able to give advice on varieties that are resistant to scab or powdery mildew. You can also check catalogs, books, magazines and fruit societies like the Home Orchard Society. And never ignore the hard-earned knowledge of experienced friends.

Chernoh recommends ‘Honey Crisp’ and ‘Liberty’ for resistance to apple scab, and ‘Pristine and ‘Enterprise’ for resistance to powdery mildew and apple scab.

If you’ve already got a tree or two planted, winter dormancy is the time for some pruning and spraying, two chores that intimidate the uninitiated. February is a good time to accomplish these tasks.

“People have a fear of pruning,” Chernoh said. “They think they’ll cause irreversible damage. But actually, trees are pretty resilient.”

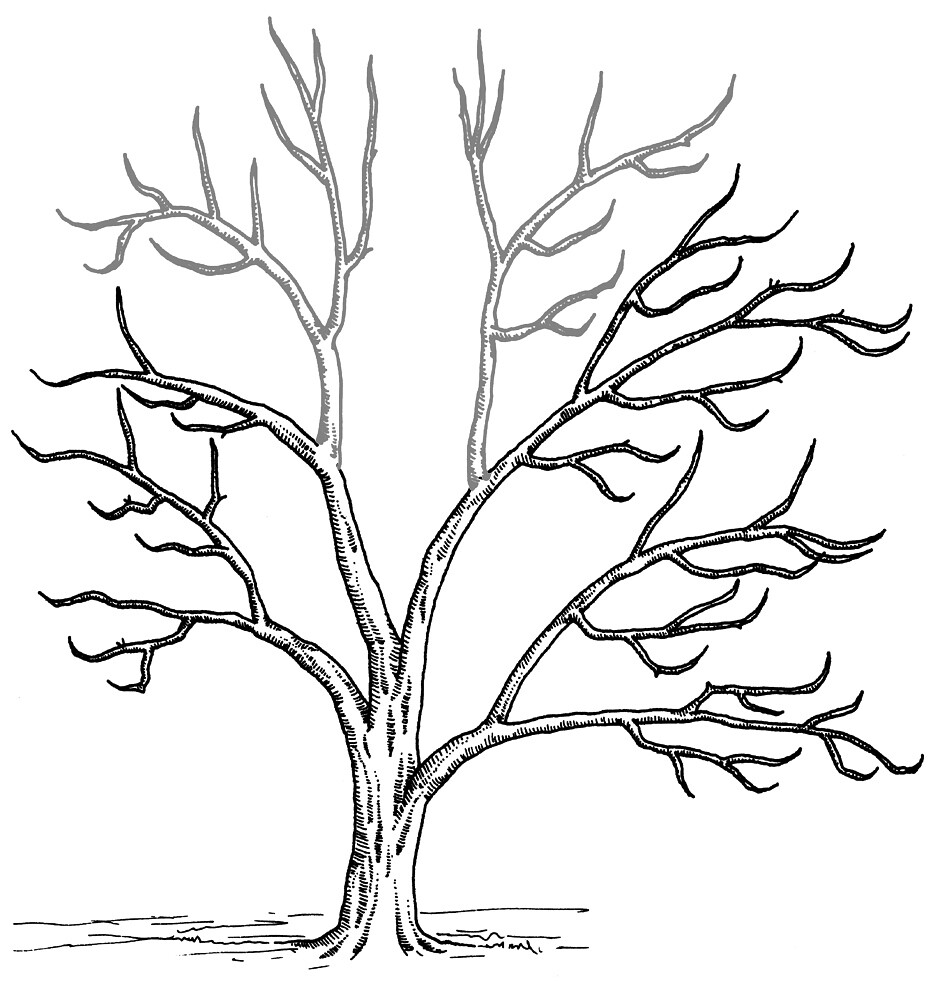

First, you have to understand the goals of pruning. It’s necessary to create a strong structure to bear a good crop of fruit and to open up the tree to assure good sun penetration and air circulation. For a new tree, Chernoh said to top it at waist height and the next year it will send out the scaffold branches that will form the tree’s framework.

For established trees: First remove dead, dying and diseased wood. Then look for water sprouts (the weak limbs that grow straight up) and thin those out. That will take care of a significant amount of pruning. Never prune more than a third of the tree in one year. After taking out the water sprouts, move on to crossed branches and cut out some of those until you hit the one-third mark.

It’s important to learn the difference between 1-year and 2-year-old wood because apples produce fruit on 2-year-old wood and spurs, which are the small, thornlike shoots that grow along the main branches. First-year is the thinner, greener wood growing at the end of a lateral branch, with circular scars or rings separating it from the 2-year-old woods. Concentrate on giving the tree a balance of both; don’t cut off just old wood or 1-year-old wood since that will become 2-year-old wood the next year and will produce fruit in the future.

“Don’t over prune,” Chernoh said. “If one-third doesn’t get all the branches that need to be removed, wait and do additional pruning during the summer or the next year when you can take another third off. Conversely, if you don’t prune at all, the tree will grow too many limbs and will produce less fruit.”

The longer you wait to prune apple trees, the harder it is to eventually get them back producing fruit. It will take several years, taking a third off a year, to restore it. The more it is neglected, the harder it is to prune.

For more help, turn to OSU Extension publications Training and Pruning Your Home Orchard and Growing Tree Fruits and Nuts in the Home Orchard. There’s even one on Pruning to Restore an Old, Neglected Apple Tree.

February is also a good time for using dormant sprays to protect trees against diseases and insect pests. Start out by reading Managing Diseases and Insects in Your Home Orchard. The dormant sprays suggested by Chernoh are allowed for organic gardening, but that doesn’t mean they are completely non-toxic.

“Applying dormant sprays is important for control of diseases like scab, or insect pests like aphids or mites,” she said. “Spraying during the dormant season is considered to be less toxic since most beneficials are less active this time of year.”

No matter what pesticide you use, read the label. It will include cautions and explain what safety measures to take like wearing long-sleeved shirts, closed-toe shoes, safety glasses and a face mask. Don’t disregard the labels, Chernoh said. Not only do they offer directions and safety precautions: It’s the law to read them and follow the directions.

For your winter dormant spraying use:

- Wettable sulfur for apple scab

- Horticultural oils for aphids, mites or scale

(Don’t use sulfur if applying a horticultural oil; the combination can be toxic to plants.)

For apple scab, do one spray now while the tree is dormant and the tips of the buds are green. Spray again later in winter when bud tips are pink, but before blossoms open. For insect pests, apply a horticultural oil in late winter to control aphids, mite eggs or scale.

Be sure to get good coverage. A backpack sprayer should be sufficient for smaller trees.

Be sure to practice good sanitation. In fall rake up leaves and rotting or mummified fruit.

Some communities offer apple pruning classes or demonstrations. Give your county Extension office a call to see if anyone is teaching a class or know of someone who is.