As bugs begin to munch our plants, our thoughts turn to – what else? – how to kill them.

Blood thirsty as that may sound, most gardeners don’t appreciate planting a garden only to have it turn into a mottled, notched or spotted mess. Sure, a certain amount of nibbling is to be expected and tolerated by gardeners who use integrated pest management, said Heather Stoven, a horticulturist with Oregon State University Extension Service. But dead plants are not.

“Accepting a little damage is important,” she said. “If you have plants, you’re always having issues. But just because you see a few insects, doesn’t mean you need to treat them immediately.”

If you’ve not heard the term, integrated pest management or IPM means using a variety of low-risk tools at your disposal to deal with pest problems and minimize risks to humans, animals and the environment. Often, waiting a few days will bring the good guys in to deal with the bad guys, especially if you’ve designed a garden with a diverse variety of plants that provide nectar and pollen.

“The biology of natural enemies is to come in as there’s an increase in a pest population,” Stoven said. “There’s a bit of a lag. But then they tend to come in and take care of the problem.”

With IPM, the most important step is to monitor your garden closely and identify pests quickly. The fewer insects, the easier it is to deal with them in the least invasive way possible.

IPM methods might include:

- Planting disease-resistant plant varieties;

- Keeping plants healthy;

- Cleaning up diseased leaves or picking pests off by hand;

- Using traps or barriers;

- Turning to the least toxic pesticides such as insecticidal soaps and horticultural oils as a last resort.

“We discourage the use of broad-spectrum insecticides for anything because good bugs and pollinators can be affected,” Stoven said.

So what to do? Follow Stoven’s recommendations to bug out those bugs the IPM way.

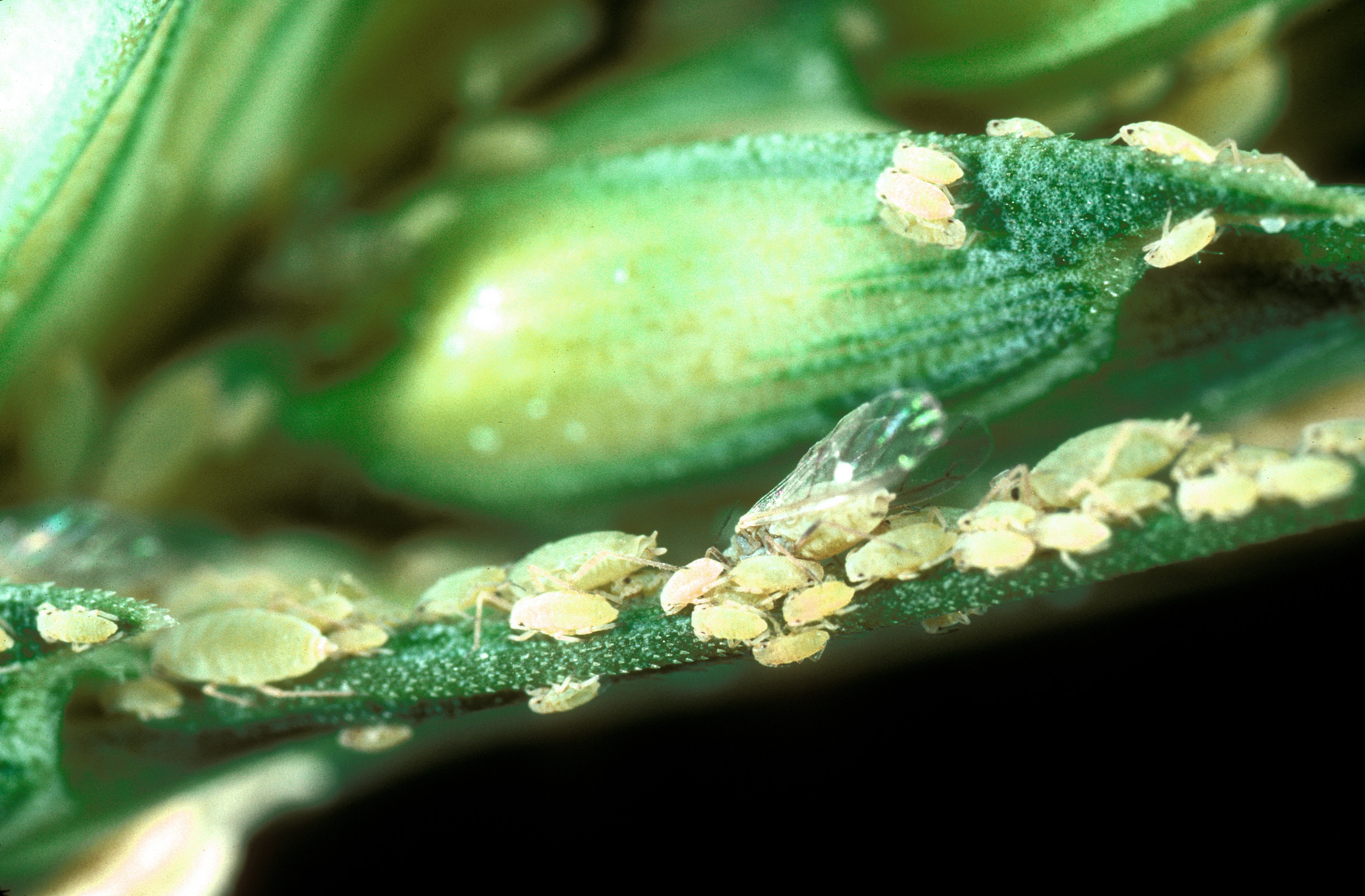

Aphids:

Probably the most common insect in gardens, aphids are small, usually light green (though there are black, gray or red aphids) and sometimes sport a fuzzy coat. They feed on plants by sucking the juice out of leaves and produce a sticky substance called honeydew.

Monitor plants often, being sure to check the underside of foliage where aphids like to congregate in large groups. To control mild populations, squish or wash off with a spray from the hose. For more moderate infestations, use commercially available insecticidal soaps. The product must come in direct contact with the aphids for effective control. Encourage natural enemies like ladybug larvae, lacewings and hover flies (syrphid flies) by not using broad-spectrum pesticides and planting a diverse variety of plants.

Azalea lace bug:

A serious pest of azaleas and rhododendrons, azalea lace bugs hatch in mid-May and the immature insects or nymphs start sucking chlorophyll out of plant leaves. They are nearly translucent light yellowish-green, darkening as they age, particularly on the abdomen. Damage shows up as a yellow, dot-like pattern on the surface of leaves and black fecal spots underneath. Large populations can suck so much chlorophyll that the foliage turns white.

Now is the perfect time to treat these bugs since the sooner you reduce the population, the less damage there will be later. Check plants often and treat with insecticidal soap or neem oil as soon as you see any insects. If the plant is small, spray with water to knock them off the plant. In both cases, be sure to get underneath foliage and be thorough. The healthier the plant, the less likely it is to get infested, so give plants proper care – partial shade and adequate water. Learn more about azalea lace bug in the Extension publication Azalea Lace Bug Biology and Management in Commercial Nurseries and Landscapes.

Crane fly:

Adult crane flies, which look like giant mosquitoes, have been showing up on screens and in houses regularly this spring. Though thought to bite people or eat mosquitoes, they do neither. In fact, they don’t do any harm at all except lay eggs that develop into larvae that chomp on roots, almost exclusively of lawns, which can tolerate quite a bit of feeding without damage.

If there are thinning areas in the lawn in spring, choose an area and dig up a 1-foot square of lawn about an inch deep. If there are 25 to 50 wormlike larvae per square foot, treatment may be necessary, but is best done in fall. Shut off irrigation after Labor Day when eggs are laid, which can reduce populations. Birds are good predators, so attract them to your yard with diverse plantings. Also, beneficial nematodes can be used in spring or early fall. Remember that nematodes are living things, so buy from a reputable source that will keep them viable, read the instructions and use them as soon as possible.

Cucumber beetle:

About ¼-inch long, yellow with black spots or stripes, the cucumber beetle is an enemy of cucumbers and squash, especially emerging seedlings. They’ll chew holes in leaves, eventually killing the plant. The beetles can also chew on flowers, reducing fruit set, and can transmit diseases.

Control cucumber beetles by planting large starts rather than seeds. Use floating row covers, which are made of very light-weight fabric that allows air, light and water through. Seal edges by burying in the soil or in some other way. The row covers are available from garden centers and online. Cover plants before infestations starts; now is the time to do that. Remove for several hours a day during flowering so plants can pollinate. Since there is more than one generation per season, it’s best to keep the the row cover on throughout the growing season.

Flea beetle:

Flea-sized, shiny and black, these insects chew tiny holes in leaves and do more damage to young plants than established ones. Three types feed on a wide range of plants, including cabbage, broccoli, kale, collards, beans, potatoes, peppers, tomatoes and eggplant.

Control the same way as cucumber beetles. More information about flea beetles is available in the publication Organic Management of Flea Beetles.

Spittle bug:

With its white, foamy covering, spittle bugs are not difficult to identify. If you can see it, the insect inside is greenish-yellow and aphid-like. Similar to aphids, these are sucking pests. Unlike aphids, they pass the juices, and it turns into the spittle that acts as a protective coating. Because of that, it’s difficult to control them with most methods, including insecticidal soaps or horticultural oil. Washing them off is the most effective method.

Though unsightly, spittle bugs don’t cause a lot of damage to plants and the adult will soon fly away.

The 2016 PNW Insect Management Handbook offers extensive information and don’t forget the trusty OSU Master Gardeners on the other end of the phone in 28 Oregon counties.

One thought on “Use natural enemies to fight bugs in the garden”

Comments are closed.

Hi Kim, I is me, the person who would rather kill a plant than a giraffe, lol. I live in Nova Scotia now. Are you familiar with Doug Tallamy’s work? Google https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B49gaeXaVbA This is two hours, but it is well worth your time. I have always required clients to include 25% natives but am revisiting that based on this information. Hugs to you, glad for the internet and to be able to follow your work.